Why Rambam?

On the 820th Anniversary of his death, some points on why he has so powerfully impacted my life and learning.

Some years ago, when I was invited to speak to the Jewish students at Cambridge University, I was graciously offered the opportunity to view select items from the Cairo Geniza. Excitedly, I walked into a room with tables upon which they had prepared various ancient manuscripts that they thought would meet my interests. They chose well. Among them was a bill of sale signed by none other than Maran, Rabbi Yosef Karo z”l, author of the Shulhan Arukh. Also included was a ketubah between a Karaite bride and Rabbinic groom which, among other stipulations, ensured that the groom would not force the bride to sit in a room lit by fire on the Sabbath. Finally, the guide, knowing of my appreciation for Rambam, handed me a single sheet encased in a clear plastic sleeve. Looking at it, I immediately recognized Rambam’s handwriting. I asked, "What is this, a letter or a message?" "No," he said, "it’s a page from the Moreh Nebukhim." Upon hearing this, I felt overwhelmed with emotion and began to cry. From eight centuries in the past, the actual handwriting of that great man who had so profoundly enlightened, lifted, and changed me was in my very hands. It was as if Rambam was standing before me, and tears of honor and gratitude welled up in humble thanks. On the 820th anniversary of his death, 20 Tebet, I share some of the reasons why his teachings have shaped my life.

The Power of Structure

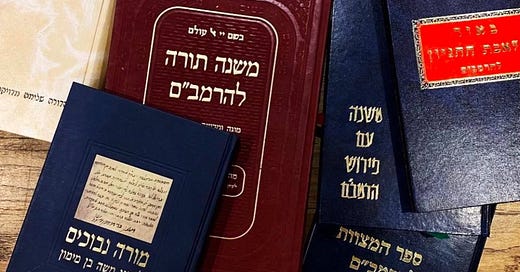

Rambam’s Mishneh Torah is a masterpiece of organization and clarity. From the vast weave of the Talmudic library, Rambam meticulously (and astonishingly) counted each commandment and gleaned each law, placing it within a specific conceptual context, inviting the reader not only to understand the details but also to consider their place in the greater framework. Rambam’s intentional review process, repeated eight times in his life, ensured meticulous accuracy. He expects his readers to notice these layers, grapple with them, and emerge with newfound insights. Such precision transforms legal texts from being a mere collection of laws into an immersive study of cohesive, contextual meaning.

Comprehensive Presentation

Maimonides sought to encompass all of Torah in his works. His goal was bold: to enable anyone to successfully study the entirety of Torah’s written and oral law by studying Mishneh Torah alongside the Five Books of Moses. His work reflects a commitment to accessibility, addressing the risks of fragmented knowledge by providing a comprehensive, clear, and universally understandable text. To this day, no work rivals Mishneh Torah in its clarity and scope. It remains an indispensable source for navigating the complexities of Jewish law and thought.

Love for Principles

Beneath Rambam’s meticulous detail lies a profound love for principles. He believed that principles are the keys to understanding and integrating the details of Torah. When we grasp the overarching concepts, the particulars find their proper place within them.

Consider his treatment of teshuba (repentance). Rambam dedicates ten chapters to elucidating the legal, spiritual and psychological process of teshuba. All of it, however, is presented as a frame for one biblical commandment: to confess sins before God after fully repenting for them. He takes the opportunity with a commandment that has teshuba as a contingent element to explain the entirety of teshuba. While the primary endeavour of the work is legal, he takes full advantage of the opportunity to flesh out a fundamental principle of Judaism in its biblical context.

Dedication to Reason

To Rambam, reason was a sacred tool for engaging with Torah and the world. He dismissed superficial readings of rabbinic texts that seemed implausible or absurd, emphasizing that the sages often spoke in riddles or parables. Failing to recognize this, he argued, dishonors their wisdom and drags Torah into folly and disrepute.

Rambam’s insistence on reason extended to his engagement with science and philosophy. He was unafraid to reinterpret scripture when logical or empirical evidence demanded it. If the world clearly demonstrated a truth, he believed it was not the Torah that was wrong but our understanding of it. In this, he upheld the unity of divine truth: the Torah and the natural world, both authored by God, cannot ultimately contradict each other.

The World as Divine Expression

Most compelling is Rambam’s view of the universe as an expression of God. To study creation is to study its Creator. The intricacies of the natural world, the human mind, and the unfolding of history are all revelations of God’s ways. In his Moreh Nebukhim, Rambam explains that God showed Moses all of creation, teaching him that the entirety of creation is a revelation of God’s ways. To love God, then, is to immerse oneself in the study and appreciation of His works by exploring the sciences, arts, and human relationships.

A Legacy of Love

Rambam’s overall vision is one of hope and love. His works remind us that the world is not arbitrary but imbued with divine purpose. To him, the world is not a distraction to be avoided, but a sacred interface with God. His path in Torah is comprehensive, consistent, deep, and penetrating.

His teachings have changed my life. He has given and continues to give me a framework through which to see and understand the entire world as an act of divine love and to respond in kind through study, action, and gratitude. This is why I regularly quote him, why his works resonate with compelling relevance 820 years later, and why I will forever be indebted to his brilliance. And for that, I love him.

Thank you Rabbi Dwecks for this beautiful reflection. The Rambams works indeed not only saved me from the path of OTD, but so enhanced the Torah that my entire paradigm changed. His Moreh and Mishneh Torah are often overlooked today, though their impact is undeniable.

Thank you Rabbi Dweck and thank you for The Habura. This was very timely for me as I had just been listening to Rabbi Wiederblank's excellent shiur "HaRambam and Mysticism" on The Habura, and his discussion of Rambam's Palace Analogy from Moreh ha-Nevuchim.